In 330 AD, Emperor Constantine’s rule extended from the Roman Empire to the Byzantine Empire, and shortly after Christianity became the dominant religion of the Empire upon his conversion to Christianity.[3] Byzantium was renamed Constantinople[4] and became the capital of both empires: the western in Rome and the eastern in Byzantium.[5]

A Flourishing Era of Churches

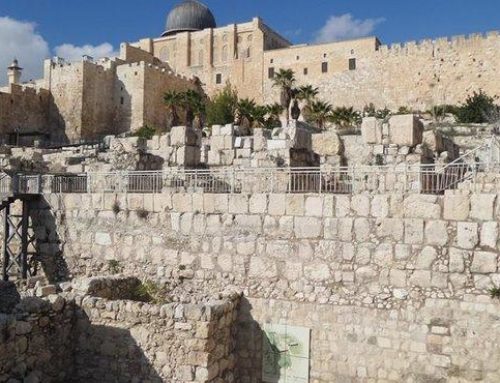

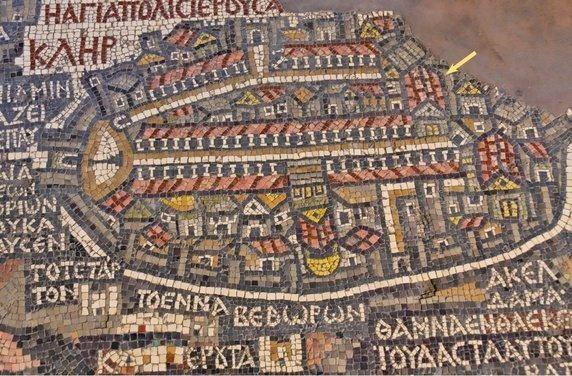

Constantine and his mother Helena ordered the erection of many churches in Jerusalem.[6] The most important church built then was the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, also referred to as the Church of Resurrection. They also ordered the building of the Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives, the Church of Martyrium midway between Jerusalem and Bethlehem,[7] and the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem.[8]

Christians once again became the dominant inhabitants of the city and they continued to establish and expand their churches. From the beginning of the rule of Empress Eudokia in 444 AD, there was a flourishing of churches.[11] The empress ordered the building of many churches including the Church of St Stephen where she is believed to be buried.[12]

Flourishing Commercial Life

With the erection of many churches in Jerusalem, the city became a center of Christian pilgrimage. The Jerusalem that witnessed the last days of Jesus according to the Christian tradition, now attracted pilgrims from different places, which resulted in the prosperity of commerce and business. Soon the city became the richest in the East.[14] he Fifth Church Council cemented the place of Jerusalem by declaring it the center for the Patriarchate.[15] However, the economic and cultural growth of the city also made it a target for invasion campaigns from the competing empire of the East, Persia.[16]

In 614 AD, the Persian emperor Chosroes II invaded Jerusalem.[17] Many Jews living in the northern parts of Palestine joined Chosroes’ invading troops and made their way into the city.[18]

Upon the capture of Jerusalem, Persians and Jews massacred Christian inhabitants, destroyed churches and took The True Cross, upon which Jesus was believed to be crucified, with them to Persia.[19]

The Persian victory, however, did not last, and ; 627-628 AD Heraclius, the emperor of Byzantium, attacked the Persians, defeated Chosroes II and restored Jerusalem to Byzantine rule again.[20] The True Cross was also taken back to Jerusalem.[21] Muslims believe that this battle between the two empires was mentioned in Quran in the chapter on the Romans (Surah al-Rum) where Quran predicted the victory of Rome after its defeat at the hands of the Persians.[22]

Once again, Heraclius followed in the footsteps of Hadrian and issued an edict forbidding the Jewish presence in the city under penalty of death.[23]

While the great empires of Persia and Byzantium were fighting over n Jerusalem, a new power emerged under Prophet Muhammad in the Arabian Peninsula that threatened both empires.[24] The new Muslim nation fought the Romans first in Mu’ta (a city in the south of present day Jordan) and shortly afterwards, defeated them in 636 AD in the battle of Yarmouk.[25]

In 637 AD the Arabs lay siege to the city of Jerusalem and one year later the Muslim Caliph Umar Bin Al-Khattab received a message that Aelia (Jerusalem) would surrender to him alone. The Patriarch of Jerusalem handed the city’s keys to the Caliph upon a guarantee of the city’s security to begin a new chapter of the city’s history.[26]

[1] Henry Cattan, Jerusalem (London: Saqi Books, 2000), 24

[2] Riad Yassin and Amjad Al-Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History of Jerusalem (Jordan: Dar Wael, 2012), 19

[3] Cattan, Jerusalem, 24 Karen Armstrong, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005), 174

[4] Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem: a History of Forty Centuries (New York: Random House, 1968), 145

[5] Aref Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Al Andalus Library, 1999 fifth edition), 71

[6] John Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome and Byzantium”, Jerusalem in History (2000): 90 and Kollek and Pearlman, a History of Forty Centuries, 145-149 and Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 187-188

[7] Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 94

[8] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25

[9] Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 193-194

[10]Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 95

[11] Kollek and Pearlman, a History of Forty Centuries, 151 and Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 206-208

[12] Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 99

[13] Kollek and Pearlman, a History of Forty Centuries, 151

[14] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25

[15] Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 76

[16] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25

[17] Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 214

[18] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25 and Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 102

[19] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25 and Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 102

[20] Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 215

[21] Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 102

[22]Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 77

[23] Cattan, Jerusalem, 25

[24]Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 216

[25] Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 102

[26] Wilkinson, “Jerusalem under Rome”, 103 and Kollek and Pearlman, a History of Forty Centuries, 152