Muslims conquered Jerusalem in 639.. Second caliph, Umar bin al-Khattab, visited the city and ordered the erection of mosques and assigned some of Muhammad’s contemporaries and companions like well-known Ubadah bin al-Samit the positions of judges and teachers in the city[1].[2] Uthman, the Caliph who took over after the murder of Umar, gifted the inhabitants of the city with the spring of Silwan as a waqf, and inspired the beginning of a culture of giving endowments in the form of public services in the city.[3].[4] After the murder of Uthman, disagreement about whether Ali bin abi Talib should be inaugurated before justice was served to the murders of Uthman caused tensions among the Muslims, and battles ensued. Eventually, the group led and supported by Aisha, the wife of the prophet Muhammad, and several of the companions, including the governor of the Levant since the reign of the first caliph, surrendered. Mu‘awiya the governor in Damascus, marked the start of the Umayyad dynasty when he declared his son Yazid would rule after him.

The Significance of Jerusalem for the Umayyad dynasty

Several Umayyad caliphs visited the city[5] and some, including Mu‘awiya, Abd al-Malik and Sulayman were even inaugurated there.[6] [7].[8] The rulers assigned to govern Palestine were often Umayyad princes who were on their way to the caliphate like Abd al-Malik and his son Sulayman or their most trusted noblemen like Umar bin Said Al-Ansari.[9]

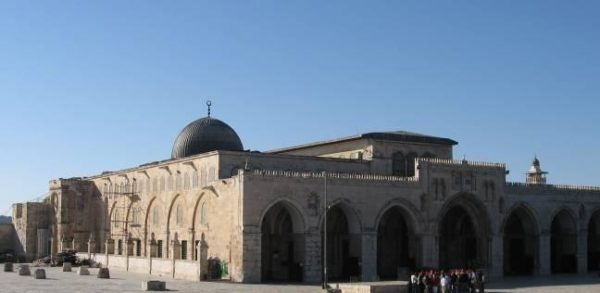

The most notable achievement of the Umayyad state in Jerusalem was the construction of Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock.[10] Abd al-Malik bin Marwan, the Umayyad Caliph whose reign extended from 685-705, ordered the construction of the Dome,[11] Historians offer differing accounts regarding the construction of the al-Aqsa mosque: many of them believe that Abd Al-Malik ordered the erection of the mosque while his son Al-Walid finished its work later in the eighth century.[12]Some call this mosque the mosque of Umar referring to the first time Umar Bin Al-Khattab prayed in Jerusalem in Al-Aqsa yard.[13]

The Umayyads supported scientific and intellectual advancement in the city and encouraged many scholars to visit the city and live in it.[18]

[1] Aref Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Al Andalus Library, 1999 fifth edition), 105

[2] Riad Yassin and Amjad Al-Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History of Jerusalem (Jordan: Dar Wael, 2012), 32

[3] Abdul Aziz Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, Jerusalem in History (2000): 108

[4] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 34 and Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 108

[5] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 35

[6] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 35 and Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 108

[7] Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 109 and Karen Armstrong, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005), 235

[8] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 35 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 116

[9] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 35

[10] Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 110 and Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 237 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 107

[11] Habib Ghanem, Jerusalem: a History and a Cause (Lebanon: Dar Al-Manhel, 2002), 30 and Joseph Millis, Jerusalem: the Illustrated History of the Holy City (London: Andre Deutsch, 2012), 35 and Teddy Kollek and Moshe Pearlman, Jerusalem: a History of Forty Centuries (New York: Random House, 1968), 156

[12] Kollek and Pearlman, a History of Forty Centuries, 161 and Armstrong, One City, Three Faiths, 242-243 ans Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 111 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 111

[13] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 30 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 116

[14] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 36 and Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 111

[15] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 37 and Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 111 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 114-115

[16] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 37

[17] Duri, “Jerusalem in the Early Islamic Period”, 111 and Al-Aref, History of Jerusalem, 114

[18] Yaseen and Fa’ouri, the Political and Cultural History, 37