Background

Upon occupying East Jerusalem in 1967, Israel sought to validate its existence in the city and cover the legal gap therein through the passage of a number of laws and decrees. The Israeli government then convened under the chairmanship of Levi Eshkol, who was the third Israeli Prime Minister, in June 11, 1967 to decide on the future of the city. The session resulted in the decision to annex East Jerusalem into Israel. The Israeli government then entrusted a ministerial committee with the task of drafting a solution to the administrative and judicial vacuum that had been created because of the decision. The governmental agencies were also tasked with dealing with the complexity that arose from the annexation, as the move spurred rejection and condemnation from the international community

.[1] On June 21, 1967 the committee introduced three draft laws to be discussed and endorsed by the Knesset four days later. The Knesset subsequently discussed and voted on the three drafts within three and a half hours. One of the aforementioned drafts was the Law and Administration Ordinance Amendment No. 11 of 1967. This article addresses this law and its effect on the City of Jerusalem. [2]

Contents

The Law and Administration Ordinance Amendment No. 11 of 1967 is comprised of two articles. The first established the application of the Israeli administrative and judicial decisions to all areas of “Israeli land,” which were to be officially declared via a decree. The second article announced the date of the Knesset vote, June 25, 1967, as the official date in which the law was to be applied.[3]

Although the ordinance itself did not mention the terms “Jerusalem” and “annexation,” the focus on Jerusalem was evident through the issue of legislative decree No. 1 by the Israeli government. Issued on June 28, 1967, the decree listed the areas where Israeli law would be applied, which included the boundaries of East Jerusalem and its surroundings, including the areas Sur Baher, Um Toba, Western Sawahrah, the Old City, Al-Jouz Valley, Sheikh Jarrah, Mesrarah, Issaweiah, Shuafat and Beit Hanina, which all were Palestinian Territories.[4]

Aim and Application

The ordinance had many goals to achieve. As mentioned prior, Israel sought to legitimize the annexation and to appease the international community by attempting to legalize the action through legislation . The ordinance, however, also aimed at changing Jerusalem’s legal status in addition to changing its geography, administration, demography and economy. [5]

The goals of the ordinance started to emerge to the public after the Israeli Defense Force issued an order to dissolve the Arab Secretariat Council, which was elected by Jerusalemites and was responsible for East Jerusalem’s administration under the Jordanian rule from 1948-1967. The army also fired Jerusalem’s Mayor Rohi Al-Khatib from his work. The Israeli forces also took over Jordanian offices, departments, records, courts, and municipality headquarters in the city, in addition to canceling their laws and regulations and replacing them with Israeli ones. .[6]

Current Boundaries

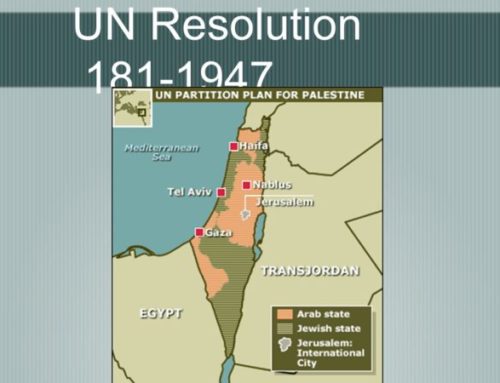

The law set the boundaries of the Jerusalem Municipality which extended from Qalandia Airport in the north, Beit Hanina in the west, Sur Baher and Beit Safafa in the south and Al-Tour, Ezareiah, and Anata in the east.[7]

As a result of the changes, 100,000 Palestinians in 72,000 Acres were under direct control of Israel within one expanded Jerusalem.[8] These individuals were termed residents of Jerusalem, yet they are not citizens of Israel, which essentially means Palestinians in the annexed areas have residency duties without citizenship rights.

[9]

Effects of the Ordinance:

The ordinance affected the reality of the city of Jerusalem in four main ways:[10]

1. Jerusalem’s area was expanded from 1326.956 acres to 26687.381 acres through the annexation of villages and towns around the city;

2. Created an Arab minority in the city by annexing low populated areas while keeping most of the Palestinians out of the boundaries of the city;

3. Increased the safety of Jerusalem for Israelis from any tension with Palestinians by including surrounding mountains as natural safeguard;

4. Separated Jerusalem from the West Bank and Gaza Strip economically, administratively and geographically in order to easily control the city.

United Nations Reaction

Upon the annexation of East Jerusalem, the United Nations issued many resolutions declaring Israeli measures in Jerusalem void and null and calling upon Israel to rescind all measures that would change Jerusalem’s legal status. Resolution 252 of May 21, 1967 considered Israel’s annexation of the city illegal, while the General Assembly and the Security Council added many other resolutions in July 1967 just after the adoption of the ordinance. These resolutions were applied to the situation in Jerusalem. Resolution 2253 of the General Assembly and Resolutions A6753 and S8052 of 1967 addressed the Israeli measures to change the status of the city of Jerusalem declaring the illegality and nullity of such measures..[11]

[1] Waleed Al-Khaledi, “Jerusalem: the Peace Key,” (Palestinian Studies Organization: Beirut: 2017) p 115

[2] Osama Halabi, The Legal Status of Jerusalem and its Arab Citizens (Lebanon: Institute of Palestine Studies, 1997p7

[3] Id p. 8

[4] Id p. 10

[5] Ibrahim Abu Jaber, “Future of Jerusalem: How to Save the City from Judaization Policies,” p 19, the paper can be found on http://refugeeacademy.org/upload/library/books/من%20نجلاء%20مقيد/مستقبل%20القدس%20وسبل%20انقاذها%20من%20التهويد.pdf

[6] Abu Jaber, Future of Jerusalem, p 20

[7] “The Occupation Laws to Control Jerusalem,” at https://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2016/4/3/قوانين-الاحتلال-للسيطرة-على-القدس posted April 3, 2016

[8] https://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2016/4/3/قوانين-الاحتلال-للسيطرة-على-القدسand halabi 10

[9] Kamal Mohammed Al-Astal, “The Future of the City of Jerusalem under the Israeli Policies to Change the Geographic and Demographic Status of the City,” the paper can be found on http://info.wafa.ps/userfiles/server/pdf/future_of_Jerusalem.pdf

[10] AlKhaledi, Jerusalem: The Peace Key, p 115

[11] UNGA resolution 2253 of July 1967 https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/A39A906C89D3E98685256C29006D4014, UNSC resolution 252 of May 1967 https://unispal.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/0/46F2803D78A0488E852560C3006023A8, and UN Resolution A6753 and S8052 of July 1967 https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.nsf/0/75F4295A2B2E2F2C0525656000754334

Picture: People looking at the Dome of the Rock at https://www.alghad.tv/الأزهر-يتبنى-دورا-أكثر-قوة-في-الدفاع-عن/