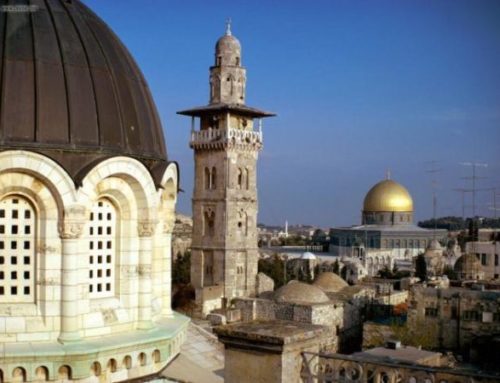

For many centuries, Jerusalem had been internationally recognized for its contributions to literature and art. Arabs, who were diversified in terms of religious orientation, used Jerusalem in their creative work, presenting the city in different frames and through different lenses, such as historical, political, social, national, and religious ones. This article is dedicated to reveal the religious dimension in the Arabic poetry about Jerusalem.

Religious Status of a Lost City

It is typical for poets to use lost cities, either destroyed or occupied, as a tool to express the emotion of longing. This is the case for the cities of Andalusia, Granada and Cordoba. However, a city with a religious affiliation, like Jerusalem, appears different in both modern and historical poetry. Such a religious status leads poets to use a more present and future tense rather than past tense when describing the city. This reveals hope and aspiration, in addition to longing and sorrow.[1] The religious dimension in the poems concerning Jerusalem appear in different levels and trends. Some of which are simple and obvious, while others need more interpretation and meditation. Poets usually use more than one theme in the same poem. For example they may use resistance as a sacred function while still deploying religious terms, events and figures to introduce Jerusalem as a spiritual center. [2]

Isra’a and Miraj

One of the main components of the religious dimension in poetry is the use of the night journey made by the Islamic Prophet Mohammad. The journey has been used by many poets to connect Jerusalem with the message of Islam and stress its sacred status for Arabs and Muslims. The Palestinian poet Abdul Rahman Barghouthi in his poem “The Journey” uses Al-Isra’a event to emphasize the connection between Jerusalem and Mecca and its holy status in Islam as he says:

To whom should the hearts express their loyalty?

To Al-Aqsa no wonder

Where the first of the two Qiblas

Where cities became united

And where Jerusalem is connected to the land of Hira’a (Mecca) .[3]

Other poets used Jerusalem in their work to illuminate the theme of leadership. In the aforementioned store, for example, Prophet Mohammad led all other prophets and messengers to prayer in Jerusalem.[4] Poets point to the Israeli oppression and compare it with the oppression the prophet faced from the Quraish tribe. In his poem “Back to Skies” the Saudi poet Jasem Al-Sehaieh says:

Again

Al-Aqsa opens a door to sky

Where people race to God

Turning Jerusalem into pure longing

… (Palestine) This bereaved free land

Gives birth to prophets

Everything in Palestine is a prophet

There is no more Jerusalem

It is currently praying in the sky[5]

A group of poets also used the story of the Al-Israa journey to urge resistance and to praise Palestinians who revolt against oppression. The Palestinian poet Shihab Mohammad uses religious terms and thoughts inspired by the Hadiths of Prophet Mohammad saying:

The ones who are on the covenants

Did not leave a promise

Nor did they renounce a covenant

The holy house, Al-Israa and Al-Miraj

Are debts they have to meet.[6]

Occupation and Absence of Worshippers in the Jerusalem

Another component of the religious dimension here is the sorrow over the absence of worshippers in Jerusalem due to the occupation restrictions. In his poem “Inspired by the Defeat”, the Syrian Badawi Al-Jabal says:

Did Aden know that Al-Aqsa is abandoned?

Where is Jerusalem, where is the city of Jesus and the station of AL-Buraq

No Quran is being recited… Muslims and Christians are prisoners alike

What a shame for Islam when Jerusalem is being looted…

Our lives have no glory, glory does not last long.[7]

The Palestinian poet Abdel Rahim Mahmoud addresses Prince Saud, warning him of the danger of the loss of Jerusalem saying, “oh prince, in front of you is a poet who suffers deep pain, did you come to visit Al-Aqsa or did you come to say goodbye before we lose it.”[8]

Hope and Unity

The religious dimension also has a trend of hope and unity within it. Poets used Jerusalem and its religious status to express their hopes to achieve unity among Arabs as to defeat the Israeli occupation in the city, the same way Islam united Arabs and allowed them to defeat their enemies in the past. The Egyptian poet Ahmed Abdel Moaty Hegazy in his poem “Beautiful Elegy Age” states:

Mohammad was above the minarets

Illuminates my way

And reconciles the horses of the Franks

Turning them into a green tree in the hills[9]

Jesus in Jerusalem

Arab and Palestinian poets also referred to Jesus as a Jerusalemite who had strong connections with the city. Jesus was used to reveal many themes such as injustice and betrayal. The Palestinian poet Fadwa Toqan in her poem “To Jesus on his Birthday” connects Jesus’ pain with that of Jerusalem by saying:

Oh Master, glory of universe

In your birthday this year

Jerusalem’s happiness is crucified

In your birthday

All bells are silenced

From a 1000 years they were not silenced

This year they are.[10]

The connection between Muslim and Christian Palestinians in Jerusalem was also introduced in poetry. The Palestinian poet Samia Al-Khalili in her poem “The Shoe of Aysha” says:

I called

I shouted

I remained the echo

Hanging in a bell of a church

And a crescent of a minaret

The dust eats me to help Jerusalem.[11]

Jerusalem has also been used in a historical context, and poetry often merged the notions of history and religion to create art. That merger will be discussed in a future article.

[1] Yusra Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry (Kuwait: Afaq, 2013), p 59

[2] Id

[3] Rida Ladadwa, Jerusalem in the Modern Palestinian Poetry (Birzeit University: 2005), p 109- 110 and Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 60

[4] Eman Masarwah, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry (Al-Manhal: 2014), p 109 and Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 60

[5] Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 61

[6] Masarwah, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 25-26

[7] Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, 63

[8] Masarwah, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 23

[9] Al-Dariey, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 66

[10] Ladadwa, Jerusalem in the Modern Palestinian Poetry, p 111

[11] Masarwah, Jerusalem in the Arab Poetry, p 25

Picture:

“My Capital” By Nabil Anani 2014 at https://rommanmag.com/view/posts/postDetails?id=4661