Facts on the Ground

On May 15th, 1948, Israel was declared a state and the British Mandate on Palestine was terminated. Battles broke out all over the area between the Israeli army and different arab armies. . Until 1949.[1]

On July 22nd, 1948, a line was drawn between the Jordanian army in the eastern part of the city– namey the Old City of Jerusalem, and the Israeli army in the western part of the city and what is known as Modern Jerusalem..[2] In the end of November of the same year, a ceasefire agreement was signed, and the final armistice agreement was reached on April 3rd, 1949. With the signature of the armistice agreement between the two parties, the division of the city into east and west became official. Israel now had control of Western Jerusalem and Jordan was commissioned to maintain Eastern Jerusalem..[3]The eastern part of the city that included the Old City of Jerusalem, however, was also annexed by Israel after the Six-Day War in 1967.[4]

ince the occupation in 1948 and with the full annexation of the city in 1967, Israel has a strict policy of Judaization in the city–systematically seeking to alter the demographic and geographic character of the city to an exclusively Jewish and Israeli one.The accomplish this by threatening the existence of Palestinians in the city through violence, excessive taxation and the expansion of settlements. .[5] In 1980, the Israeli Knesset that declared Jerusalem the united and eternal capital of Israel.[6]

The Legal Status of Jerusalem

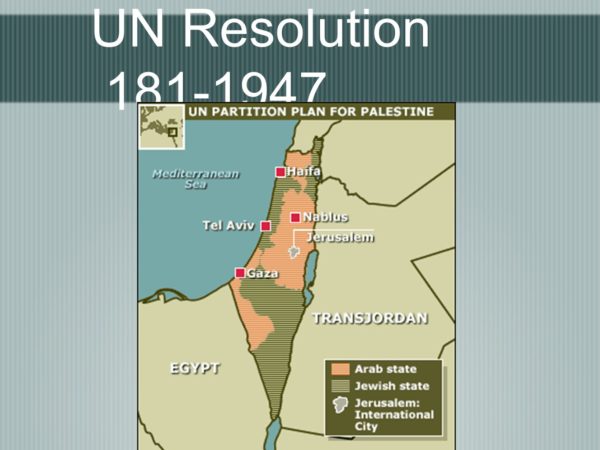

Resolution 181 of the UN General Assembly, which was issued in November 1947 declares the termination of the British Mandate over Palestine and its replacement with a partition of the territory based on the principle of self-determination for two peoples.[7] . The city was declared, according to the resolution, a “Corpus Separatum” or a special independent city with international legal status.[8] The resolution stated that existing local autonomous units in the city territory, including the municipality, towns, and villages would enjoy wide powers of government and administration. It also called for the demilitarization of the city and the preservation of its neutrality. The UN further recommended that a legislative council organize all the city’s internal and external administrative affairs.[9]

The resolution provided the geographic boundaries of the corpus separatum and included in it the city of Jerusalem, its surrounding villages and towns whose boundaries extended from the municipality from Abu Dis in the east, Bethlehem in the south, Ein Karem in the west, to Shufat in the north.[10]

This resolution was meant to offer a temporary, ten year solution after which the people of Jerusalem would determine its future under the supervision of the UN Trusteeship Council.[11]

Lack of Applicability but Not of Legal Effect

The resolution was not practically applied due to many factors including the Israeli occupation of the city and its expansion beyond what was determined in the resolution, the rejection of the resolution by Palestinians represented by Arab Higher Committee (National Higher Committee), the signature of armistice agreements by the Arab Governments participating in the fight and Israeli Government, and the agreement to unify the West bank and Jordan in the conference of Jericho on April 11, 1950 which extended Jordanian rule to the West Bank, which included East Jerusalem. The agreement however, meant that both Jordanian and Israeli rule over the city violated its legal status as presented in Resolution 181. .[12]

The provisions of the resolution that laid down the principle of internalization remained unimpaired while the provisions that dealt with the administration were frustrated by the occupation of the city.[13] Because neither the violation nor the lack of implementation of a UN resolution entails its abrogation– resolution 181 continues to be valid and binding.[14]

Reaffirmation of the resolution

he UN reaffirmed Resolution 181 in a number of subsequent resolutions.[15] For example, the General Assembly’s Resolution 194, signed on December 11, 1948 and Resolution 303, which was signed on December 9, 1949 both affirm the validity of Resolution 181 although both were passed after the division of Jerusalem between Israel and Jordan .[16]

Moreover, both the General Assembly and the Security Council issued resolutions that condemn the Israeli occupation and the annexation of Jerusalem and declare all Israeli measures that violate Jerusalem’s legal status null and void.[17] Some examples of such resolutions are General Assembly resolutions 532 of 1977 and 2253 of 1967, as well as the Security Council resolutions 252 of 1968, 452 of 1979, 465 of 1980, 476 of 1980,[18] 267 of 1969, 271 of 1969, and 298 of 1971.[19]

Israel’s occupation of Jerusalem and annexation of its lands both in 1948 and in 1967, in addition to all of its policies and measures whether legislative, administrative, demographic, or geographic taken to change the legal status of the city are null and void according to the decisions of the international legitimacy represented by the United Nations’ different organs.[20] Such condemnation and rejection of such Israeli measures in the city are important because they reinforce the legal effects of resolution 181 and declare the international status of the city effective even though 181 was never actually applied.[21]

Israel and Resolution 181

The State of Israel was declared legal only after the adoption of Resolution 181, so its refusal to comply with it is ironic, to say the least..[22] Not only did Israel accept the resolution initially, but also acknowledged that Jerusalem has a different legal status than other Palestinian cities and towns.[23]

Sovereignty over Jerusalem

It is important to note that according to international law, Palestinians alone have sovereignty over Palestine and that Resolution 181 does not negate that sovereignty in Jerusalem nor does it strip from them their legislative, judicial, or taxation powers.[24]Not only that, but Palestinians are not bound by the provisions of the resolution upon their absence of acceptance.[25]

On the other hand, any Israeli claim or presence in the city is in direct violation of international law.

[1] Osama Halabi, The Legal Status of Jerusalem and its Arab Citizens (Lebanon: Institute of Palestine Studies, 1997), 45

[2] Halabi, The Legal Status, 45

[3] Halabi, The Legal Status, 46

[4] Habib Ghanem, Jerusalem: a History and a Cause (Lebanon: Dar Al-Manhel, 2002), 194-195

[5]Ghanem, Jerusalem, 204-205

[6] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 203-204

[7] Henry Cattan, Jerusalem (London: Saqi Books, 2000), 104

[8] Halabi, The Legal Status, 46 and Ghanem, Jerusalem, 194

[9] Qattan, Jerusalem, 104-105

[10] Halabi, The Legal Status, 46

[11]Gershon Baskin, Jerusalem of Peace: Sovereignty and Territory in Jerusalem’s Future (Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information, 1994), 17 and Ghanem, Jerusalem, 200

[12] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 210 and Cattan, Jerusalem 110

[13] Cattan, Jerusalem, 105

[14] Halabi, The Legal Status, 46-47 and Cattan, Jerusalem, 106

[15] Cattan, Jerusalem, 108

[16] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 210 and Cattan, Jerusalem, 105

[17] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 211 and Cattan, Jerusalem, 109

[18] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 211

[19] Cattan, Jerusalem, 109

[20] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 213

[21] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 213 and Cattan, Jerusalem, 110

[22] Cattan, Jerusalem, 107

[23] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 213 and Cattan, Jerusalem, 107

[24] Ghanem, Jerusalem, 210

[25] Cattan, Jerusalem, 108